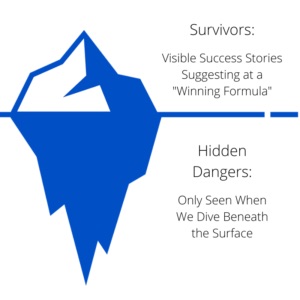

Survivor’s bias is a phenomenon typically observed in the financial sector where people tend to place the emphasis on the winners or survivors within a given system. But it is a mistake to only analyze winners. By only focusing on the winners, you neglect to discover the real reasons concerning failures within that system, as you neglect those failed or lower-level parties that are involved within that system as well.

It can lead to overly optimistic beliefs because failures are ignored, such as when a gymnast is no longer in the program and therefore excluded from analyses. This can also lead to the false belief that the successes in a group have some special property, rather than just coincidence (correlation “proves” causality). For example, if three of the top gymnasts from the National Team all went to the same junior club that can lead one to believe that the club must offer an excellent program or coaching when, in fact, it may be they just draw from a larger population. This can be better understood by looking at the performance of all the other gymnasts from that club, not just the ones who made it through the selection process.

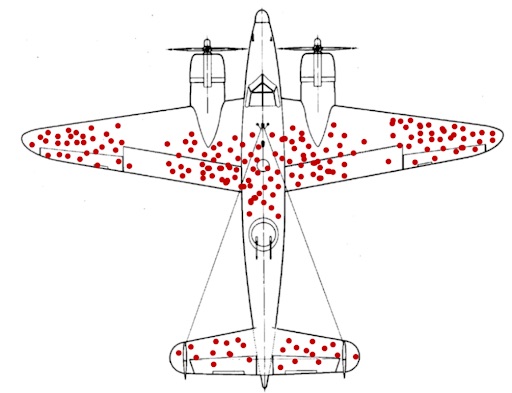

The most famous example is that During World War II, the statistician Abraham Wald took survivorship bias into his calculations when considering how to minimize bomber losses to enemy fire. The Statistical Research Group (SRG) at Columbia University, which Wald was a part of, examined the damage done to aircraft that had returned from missions and recommended adding armor to the areas that showed the least damage. This contradicted the US military’s conclusion that the most-hit areas of the plane needed additional armor. Wald noted that the military only considered the aircraft that had survived their missions – ignoring any bombers that had been shot down or otherwise lost, and thus also been rendered unavailable for assessment. The bullet holes in the returning aircraft represented areas where a bomber could take damage and still fly well enough to return safely to base. Therefore, Wald proposed that the Navy reinforce areas where the returning aircraft were unscathed, inferring that planes hit in those areas were the ones most likely to be lost. His work is considered seminal in the then-nascent discipline of operational research.

A gymnastics example of a distinct mode of survivorship bias or that correlation “proves” causality would be thinking that a technical plan or preparation plan for a specific skill worked because everyone who is currently doing the skill in your gym uses that same technique. Even if you know that some people were unsuccessful, they would not have their voice to add to the conversation, leading to bias in the conversation. When I was a “rookie” coach I had four gymnasts who were very fast learners on uneven bars. I, of course, took all the credit for this. I am a GREAT bar coach. When they graduated and I had to work with other groups who were following the same plan I quickly realized that the success of the previous group was based more on their talent and body type than on my plan and technical corrections. With this new group I had to work twice as hard, make adjustments to the plan and technique to have a similar result.

Becoming a successful athlete is an admirable aspiration, but it’s important to keep a sense of perspective. Only 5 of the 1.2 million youth gymnasts in the USA are likely to reach their goal and make it as an olympian. That is less than 0.0005% of gymnasts who will reach their goal. Does that make them a “failure”? To some it does. What the USA does very well is through its Developmental Program (formally known as Junior Olympic or J.O. Program) giving ways for these gymnasts to compete to a fairly high level and possibly into college. At the highest level, Level 10, you can see some of the same difficulty levels as the International level. For reasons unknown, these gymnasts have decided to not take the international route. With out this program I feel that many, many gymnasts would just drop out when they see that their olympic goals are unattainable.

Losing sight of the overall statistics and ignoring the objective chances of success is a common mistake when following big role models. With Survivorship Bias people overestimating their likelihood of succeeding by focusing on a few lucky overachievers or “survivors,” who managed to beat the odds. Sure, a handful of outstanding athletes like Simone Biles fulfill their dreams of winning multiple Olympic medals. However, these athletes are the exception, not the rule. They represent rare outliers on the normal distribution curve of athletic achievement. A Ford and a Ferrari are both cars. Realistically only one of them has a chance at winning, or even competing, in Formula 1.

While evidence for survivorship bias is plentiful, you may question its negative consequences. Surely, role models can be strong motivators, inspiring ordinary people to surpass themselves, grow inner strength and discipline, and persevere during adverse circumstances? Especially in the context of sports, this must be considered an advantage.

It is true that survivorship bias can be a key source of motivation. Nevertheless, a number of dangerous consequences for people’s decision-making must not be underestimated. These include:

Neglecting reasons for failure: The singular focus on lucky over performers distracts from the many people who tried to achieve similar goals but failed. People tend to analyze reasons for success in the survivors, and disregard reasons for failure in those who didn’t make it. For instance, when a gymnast first makes the National Team, they try to emulate the skills of the highest level gymnast and forget to pay attention to everyday hurdles such as maintaining strength and basics.

Taking disproportionate risks: By overlooking the baseline probabilities of success, people may be misled into taking disproportionately large risks. Passionate amateur gymnasts, for example, may be tempted into abandoning their education to focus on their careers. They often end up regretting their risky choices afterwards.

Not knowing when to give up: The motivation to pursue a goal at all costs can turn out to be dangerous if people fail to recognize when it’s time to give up. Coaches who do not keep this in mind with the aspiring gymnasts they work with may end up pushing beyond their capabilities and sustaining dangerous injuries.

As a passionate gymnastics coach, I am all too aware of the risks associated with survivorship bias. Sure, I’d love to have a crew of Olympic and World Champions. But it’s important to stay realistic. Keeping a sense of perspective is essential for harnessing the positive motivational aspects of having role models, while managing the dangers associated with more serious forms of survivorship bias.

As gymnastics professionals we need to avoid the misconception that by focusing on the one surviving example, the most successful example, you too will be successful.

“If the best team does this, it must work, right?” We do not want to reinvent the wheel, nor do we want to blindly do what another team or gymnast does because they are “successful”. From a technical perspective I have seen coaches fall into this same trap in the gym trying to follow the technique used by the best gymnast. Once you get past technical basics gymnasts typically need to find their own functional path. Not every gymnasts is going to be able to swing like Suni or tumble like Simone.

Coaches can guard against this bias by simply being aware it exists. Rare is the coach that does not second guess his/her methods and Survivorship Bias is a big culprit in the tendency to question oneself.

Another principle stolen from the business world is The Peter Principle. No industry suffers the Peter Principle more than sport. The Peter principle is a concept in management developed by Laurence J. Peter, which observes that people in a hierarchy tend to rise to their “maximum level of incompetence”: employees are promoted based on their success in previous jobs until they reach a level at which they are no longer competent, as skills in one job do not necessarily translate to another. It is one thing to be a passionate recreational gymnast. Maybe even a a top level national athlete. However, training and competing at an international level requires a nearly completely different mindset, and level of commitment. Without keeping this in mind are we setting many gymnasts up for failure. Are we bring gymnasts up to the national team only to fail?

In gymnastics, gymnasts are continually promoted until they fail. It is an odd sport because the rules constantly evolve and goal line is constantly moving. In my career I have seen more than a few gymnast drop out after one Olympics because they are not prepared for the requirements of the new code of points.

As coaches and educators we need to continue to focus on basics and multilateral development throughout an athletes career. I have seen the pitfalls of this most recently with the gymnasts I have worked with in Italy. They completely ignored dismounts for nearly 4 years. Now they are struggling to end with a D to gain that valuable bonus.

Similar to survivor bias, a coach can guard against the negative effects of the Peter Principle by knowing it exists. Focus on BOTH long and short term goals. Continue with basic skills, multilateral development and above all, TAKE YOUR TIME. The RUSH to have your gymnast achieve a skill or a spot on the National Team may insure their ultimate failure.

I have covered two business philosophies relating them to our sport. You must have your eyes open to inherent bias and promotion until failure.