An intriguing article from The Boston Globe.

By Kay Lazar

For Kim Goodwin, the proof is in the pool.

Goodwin, a swimming coach at Norwood High School, has witnessed ninth-grade boys with little experience muscle through a 100-yard freestyle competition to beat female teammates who have been training for years.

“Some of the boys who were beating the girls had terrible technique, but they had explosive speed,” said Goodwin, herself an accomplished swimmer with national titles. “Their feet are bigger and their hands are bigger and that is huge in swimming.”

The gender gap that Goodwin observed has fascinated scientists for decades.

Research at Indiana University is yielding some of the freshest evidence on how age — and hormones — factor into sports performance. The scientists found no difference in swimming performance in children through age 7. And they pinpointed little differences among 11- and 12-year-olds.

But that started to charge with the arrival of adolescence. The scientists — who analyzed data from nearly 2 million swims by youngsters age 6 to 19 who competed from 2005 to 2010 — found that the effects of puberty on performance began showing around age 13, as the boys started experiencing accelerated height, weight, and strength.

After puberty, males have historically outrun, outjumped, outvaulted, outswum, and generally notched superior athletic performances. But researchers have long hypothesized that more access for women to training opportunities since the 1970s would squeeze that gender gap until the chasm eventually disappeared.

Two events at the just-concluded Summer Olympics highlighted that tantalizing possibility.

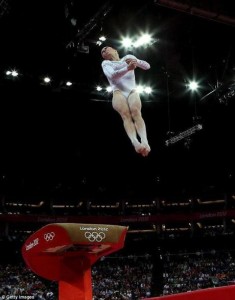

One was the height reached by US gymnast McKayla Maroney in the women’s vault event, higher even than gold medal gymnast Kohei Uchimura of Japan in the men’s vault.

The other was the jaw-dropping speed of Ye Shiwen, the 16-year-old Chinese swimmer who not only won gold in the women’s 400 meter individual medley in record time, but also swam the final 50 meters faster than Ryan Lochte, the US swimmer who won gold in the men’s 400-meter event that same night.

Some swimming officials have said the teen’s time was so unbelievable they suspected she might be taking performance enhancing drugs, which are prohibited in the Olympics. Ye denied the accusations, and drug tests appeared to back her up, coming back negative.

Dr. David Geier, director of sports medicine at Medical University of South Carolina, said he would not be surprised to see a few rare cases of elite female athletes besting their male counterparts. Such instances, he said, would most likely happen in swimming and gymnastics, sports that require flexibility, a trait more common in females.

“Swimming is about skill and mechanics, and there is an element of flexibility that requires a tremendous amount of shoulder rotation,” Geier said. “I am reluctant to say no woman could catch a man, but I would think it would have to be the right sport and the right circumstances.”

British researchers in 2004 published a paper in the journal Nature that analyzed race times in the Olympic 100-meter sprint from 1900 through 2004 and concluded that if the trend continued, the female winner in the year 2156 could notch a faster finish than the top male.

But a 2010 study by French researchers published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine compared a century’s worth of best performances by the top 10 male and female Olympic athletes across 82 sports and found that after a significant shrinking of the gap, women’s performance, on average, has not gained ground on men’s since 1983.

They concluded that more athletic opportunities for women, along with rising use of performance enhancing drugs during the 1970s and early ’80s, rapidly shrank the gap. Then regulators improved detection of prohibited drugs, leading to less drug doping, the researchers said. Female athletes’ swift gains stalled to where they remain today, about 10 percent behind male performances, on average.

“These results,” the scientists concluded, “suggest that women will not run, jump, swim, or ride as fast as men.”

Much of the doping in decades past involved anabolic steroids, a drug that mimics the effects of testosterone in the body. Because women naturally have much lower levels, female athletes in particular would benefit from steroid use.

Bottom line, say exercise specialists, is that Mother Nature is the ultimate doper, imbuing males with testosterone, a hormone that makes them more powerful and allows them to inevitably trump females’ athletic performances.

For starters, testosterone helps men carry more oxygen in their blood to feed their muscles.

“If you look at pure physiology, men definitely have an advantage,” said Polly de Mille, an exercise specialist at the Women’s Sports Medicine Center in New York’s Hospital for Special Surgery. “They have wider lungs, bigger airways, and a bigger heart that will pump more blood with each beat.”

Which brings us back to the pool at Norwood High.

Goodwin has found that several of the boys, who were novice swimmers and struggled to keep up with their more experienced female teammates in the longer events, now appear poised to overtake them. Those veteran girls initially held the edge in longer distances because technique and training can be as crucial as raw power in those events. But with a few years’ training for the male teammates, the traditional gender gap emerged.

Norwood is among a small number of Massachusetts high schools with boys competing on the girl’s swim team. Massachusetts law requires equal access to sports for both genders. Most schools typically offer a fall swimming season for girls, and have both boys’ and girls’ teams in the winter. But some districts, such as Norwood, offer just one team and one season because of budget constraints and having to share a pool with a nearby town, hence the mixed-gender Norwood swim team.

That arrangement created national headlines last fall when a Norwood boy, Will Higgins, smashed a meet record for the girls’ 50-yard freestyle event that was set 26 years earlier, by a female.

Some charged that it was fundamentally unfair for men to compete with women — and strip them of records — given the physiological differences.

Goodwin, Higgins’s coach, is torn.

“As a coach, you are thrilled with the hard work and watching it pay off,” she said. “But it’s going to be harder for the girls on the team.”

That’s because the boys’ increasingly faster times, as they catch up in training, will knock some of their female teammates out of events in local girls’ swim meets.

But the brouhaha from last fall’s upset prompted the Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association to change its rules, and for the first time during the fall season, the small number of boys who compete on girls’ swim teams will only be allowed to compete with other boys in state tournaments. They will have their own mini-tournament, with perhaps a dozen or so competing.

Association spokesman Paul Wetzel said the organization changed the rules for tournaments because it concluded a gender gap continues to exist.

Performance results “will always reflect that,” Wetzel said