-Brandi Smith-Young, PT, FAAOMPT, OCS. Perfect10.0 Physical Therapy

How To Avoid Tendon Rupture

All too often little aches in the tendon go treat with ice, stretching, and continued repetitive stresses of tumbling and vaulting. The newest studies out there now show there is no inflammatory response in tendon injuries. It is more of repetitive micro-tearing of the tendon which leads to rupture. This is no longer referred to as tendonitis but tendonopathy. This can be prevented with proper early intervention, physical therapy, and respect for the 11-12 week healing process for the tendon. Thus tumbling on the tumble track, decreasing landings and take-offs, and utilizing equipment advancements like sting mats, pits, and other absorbing equipment during the healing process is necessary. It is imperative that the cause of the tendon injury is addressed, whatever weakness or tightness is leading to abnormal stresses on the tendon. This is addressed with very specific physical therapy. If the cause of the tendonopathy is not addressed the injury will continue to return.

How can I tell it is a tendon injury verses a bone or joint?

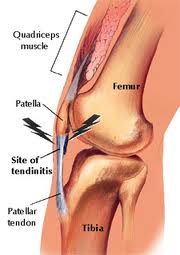

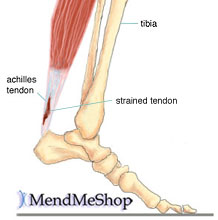

The gymnast will point directly at the body of their tendon or on it’s insertion on the bone or growth plate in a growing athlete as the location of pain. This may be the patellar tendon, just at the bottom of the knee cap, at the insertion of the patellar tendon on the tibia, the achilles tendon, or the insertion of the achilles tendon on the heel. These are the two most likely tendons injured in gymnast. Many times Severe’s Disease, Osgood Schlatter’s disease, Sinding Larsen Johansson’s disease or jumper’s knee are missed diagnosed when it may be a tendon injury or the tendon may be involved in the diagnosis.

What are the signs my gymnast is getting a tendon injury or progressing toward rupture?

- Early stages: In the early stages your athlete will report pain at the beginning of activities. Prime example would be reports of pain in the tendon or insertion during warm-ups which subside after getting “warmed-up”. No pain during actual practice. Reports of pain and the need to ice the tendon after practice. May or may not have any swelling present.

- Progressing towards rupture: As the micro-tearing gets worse the intensity and frequency of tendon pain will get worse. The athlete will report pain not only during warm-up but throughout practice, progressively worsening as impact activities (ie tumbling or vault) become more repetitive. There may be noticeable swelling over the tendon region decreased with rest, low loading (ie bike), and ice.

- End stages just before rupture: As micro-tearing worsens the athlete will start to have pain, possibly a dull ache, with most all activities. There will be noticeable swelling over the tendon which may or may not subside with rest, ice, or biking. If the athlete has not gotten treatment and limited their activities, it is necessary they do so.

- Partial tearing: When a partial tear is present or occurs. The athlete will have increased swelling which may or may not subside with ice. Possible mild bruising. Increased pain intensity and will not tolerate palpation of the tendon. Strength will still be present but painful to contract the muscles (ie. quad for the patellar tendon, gastroc for the achilles). No sports and get the athlete into the orthopedic as soon as possible for assessment.

- Full Rupture: When full rupture occurs the athlete will not be able to activate their quad or gastroc. They may get a small bit of motion from other secondary muscles( ie the posterior tibialis which also points the toe). There may be a palpable deficit in the muscle. There will be severe pain, swelling, bruising, and inability to weight bear. Immobilize the athlete, non-weightbearing, and get them into a good sports orthopedic surgeon as soon as possible. Do not have the athlete continue to contract the muscle. We do not want the muscle belly to retract any further than it already has to assist in any surgical repair needed.

What can I do as a coach to prevent the progression?

When a gymnast complains of tendon pain and is in the early stages this is the time to get the athlete in to see a good physical therapist. We will need to start the tendon training process and address the issues which have contributed to the tendon injury in the first place. In many cases it is a loading issue. The athlete is landing or jumping with poor technique or lots of compensations. Many times this is after the athlete has grown in the last year and the muscles are imbalanced. Some muscles are too tight and week while others are flexible and strong. In some cases the athlete developed compensatory movement patterns when increasing skill level and/or intensity of training. These compensations will need to be addressed along with tendon training. Tendon training involves low loading lots of repetitions (40-60% 1 repetition max, sets of 100-200 slow repetitions many times in a day). This means lots of biking, eliptical, painfree active range of motion, and minimal loading for up to 11-12 weeks. The sooner the injury is caught the faster the recovery. The stage of injury the athlete is in will dictate the amount rest from high impact activities (ie tumbling, vault, and possibly some beam tumbling or dismounts) needed. The painfree principle applies. The athlete cannot have pain while doing anything. Pain is a sign of continued microtearing and will lead to rupture. Rehab post-surgical repair of a rupture is 6-8 months and even up to 1 year to return to high level impacts and performance. As frustrating as 11-12 weeks can be the wait is worth it compared to the alternative. With proper strength and flexibility training specific to each athlete and proper tendon training your athlete will be back on track.

Look for exercises to come to help prevent tendon injuries by a proper stretching regimen and improving muscle function to promote proper jump and landing mechanics.

See the link below for presentation on tendonopathy leading to tendon rupture.